Fifteenth Sunday after Pentecost, Proper 18A

In the name of the God of clarity and revelation. Amen.

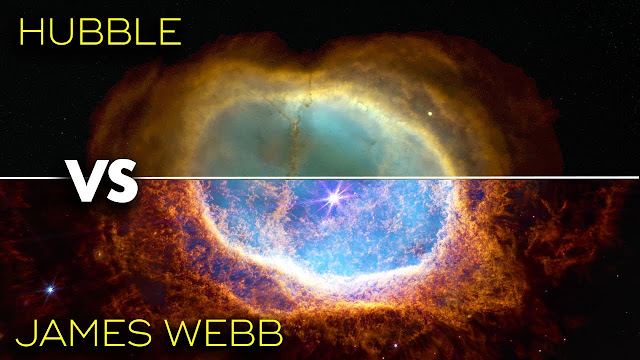

The images from the new Webb telescope that periodically come out in the news sometimes sets my mind back to remembering when the Hubble telescope first came on the scene. Its first images were transmitted in 1990, but of course, a lot of my first memories about that telescope are around the scandals that accompanied it in its earliest days. Remember? The images came back blurry. I don’t remember all the details, but there was something about the mirror that was installed – it was formed incorrectly or had some flaws. It was eventually corrected, but people couldn’t imagine how this hugely expensive project, years in the making, could have been fumbled so badly from the beginning.

But when the images started coming in, it’s like the scandal all but faded away. The telescope was orbiting the earth, above the atmosphere, so its images were free of the distortions that we had previously seen. I couldn’t possibly explain it – you’d need physicists and astronomers and engineers for that. But what I do remember, is that for the first time, we were seeing the universe with previously unimagined clarity.

Unimagined clarity, that is, until this latest telescope went in: the James Webb telescope.

Some of the most remarkable images – for me, at least – are those that show the same views that the Hubble Telescope had captured, compared to the capabilities and clarity of the Webb Telescope. The Hubble Telescope showed millions of tiny dots of light that gave us a sense of the vastness of the universe. But with the Webb telescope, we could see the definition in each of those tiny dots – we could actually see what the scientists had been telling us, that each of those dots was a galaxy unto itself, each one made up of millions of stars.

We were seeing the same thing but with new eyes. In reality, it was essentially the same information, but with a new understanding.

That’s how it feels for me when I encounter one of these biblical stories that I feel like I know inside and out, but then suddenly have a new understanding of what it might mean. The story is the same. I’m reading the same words, but suddenly it means something new to me.

I’ve often pointed to the Gospel lesson that we read today as one that I really enjoy because it’s one of those rare times when it seems like Jesus is actually just saying what he means out in the open. It’s not shrouded in an atmosphere of metaphor and innuendo. It’s a practical, how-to guide for dealing with one of life’s actual problems: how to deal with conflict in Christian community. And Christians, just like any other group of people, sometimes find themselves in disagreements. Following Christ offers us a path for how to deal with it in a healthy way, but it doesn’t make us immune from this aspect of the human condition.

The pattern is pretty simple and effective. First, when you notice that there’s a conflict, talk to the person. Don’t campaign behind their back. Don’t gossip. Don’t triangulate or obfuscate. Don’t ignore it and pray it will go away. Look them in the eye and be honest. Very often that will be enough to work out our differences.

But it won’t always be enough. Sometimes we need reinforcements. So, if talking it out doesn’t work, bring in some fresh eyes: one or two people who can hear what you’re hearing and try to help. They may be able to communicate with the other person in a way that you can’t. They may be able to show you something that you’d been missing – something that can bring resolution where you weren’t able to do it alone.

This is the basic structure of conflict transformation that I learned about in a Mediation Skills training sponsored by our diocese last year. The mediator is trained to be one of those people brought in to facilitate a conversation where direct, person-to-person conflict management has failed.

But even mediation isn’t a guarantee of a successful or desirable outcome. Even mediation can fail. So Jesus teaches that when that happens, broaden the scope. Share it with the church – with the wider community. And if even that isn’t enough to repair the conflict, then the other person should be to you like a gentile or a tax collector.

So what does that mean? At that point, they are like one outside the community. They are separated.

Here’s where my understanding this week came through the Webb telescope instead of the old Hubble: I’d always hear that sort of the way that I hear about it in Amish communities. When reconciliation proves impossible through the established protocols – then “let such a one be to you as a Gentile and a tax collector” – let them be shunned. They have proven themselves to be outside the fold, so let them be outside the fold.

It’s harsh.

But the clearer understanding that suddenly dawned on me this week was this: I asked myself, how did Jesus treat gentiles and tax collectors?

Over and over again, throughout the gospels, we hear stories of Jesus working to incorporate those who were on the margins. The gentile woman who wanted healing for her daughter. Zacchaeus, the tax collector with whom Jesus shared a meal. The woman at the well, who was accused of having questionable morals, but who became an evangelist for Christ.

Being to us as a gentile or a tax collector doesn’t mean being shunned. It doesn’t mean embracing their place as outsiders. In fact, it means we have to work harder to show these “others” that they, too, are beloved children of God. They, too, are worthy of the love of Christ. They, too, are integral parts of the community of faith and the Body of Christ.

That’s the end of the process. Not washing our hands of them. Not shaking off the dust from our feet. The end of the process is to love more – to incorporate more – to work even harder to welcome and include those on the outside.

Now, that doesn’t mean that we’re supposed to be doormats. It doesn’t mean we’re off the hook. If anything, it means we’re even more on the hook. Because loving in the face of adversity is even harder than loving when it’s all warm and fuzzy. But that’s how Jesus modeled this life for us. That’s how Jesus modeled what it means to interact with someone who seems to be an outsider.

Those words were always there, but it wasn’t until now that I could see them with this new kind of clarity. And that’s why we, who practice the Christian life, are always called to be striving for more – striving for greater depths of growth. Just like technology needs to keep evolving, so, too, do we need to keep studying the teachings of Jesus. New truth and new understanding can emerge from seemingly out of nowhere. What we thought we knew can suddenly become entirely new.

That is the mystery of wisdom in Christ. All that we know makes us ready to encounter all that we don’t yet know. Just like the love that Christ modeled, there’s always more. Amen.

Comments